How does Superman know where he isn’t?

A bird, a plane, a cruise missile, they all have one thing in common, they need to know where they are (or aren’t). But Superman doesn’t have pockets to keep his phone in, how could he possibly know where he’s going?

Moon Safari #4⌗

Before you can go somewhere, you need to figure out where you are. We instinctively rely on describing our position relative to objects that the person we’re trying to communicate with knows about. “In my room”, “on my bed”, “under the Eiffel Tower”. The more stationary and universally recognised the landmark of choice, the more meaningful our description of position.

But what if there is nothing stationary around you, what if everywhere you looked, was practically the same. What do you use to orient yourself? You look a little harder of course, after all this is something our seafaring species has spent millenia perfecting.

Birds seem to know where they’re headed, so we just tagged along behind them. Navigators seeking land sail opposite the birds’ path in the morning and with them at night (they need to rest), especially relying on large groups of birds, and keeping in mind changes during nesting season. Some cultures like the Polynesian navigators used songs and mythological stories as mnemonics to remember what to do. But staying in the splash zone under a flock of well-fed seagulls wouldn’t make for a pleasant cruise, we can do better.

Stars are so unfathomably far away, that for all practical purposes they are about as stationary and universally recognised as it gets. Although stars hold fixed celestial positions year round, their rising time changes with the seasons. You can set your heading to a specific star at the horizon and shift to a different star when it rises too high. You could then memorise the order of stars to follow and build a route. Of course to figure out which star you are looking at, you could draw patterns and shapes in the sky and give them names and insert them into stories to remember what to do.

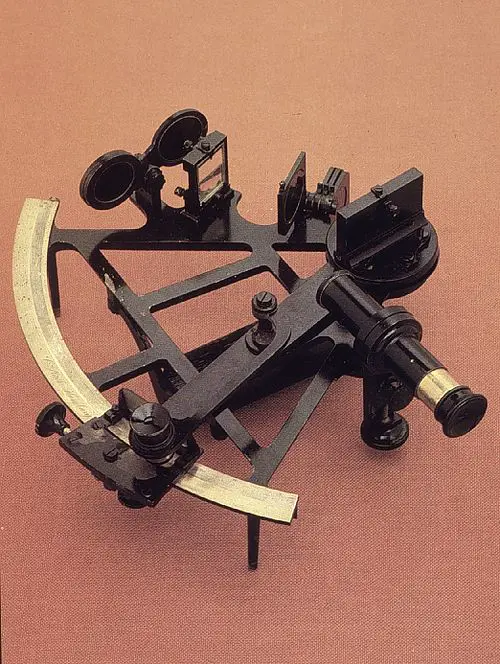

So lets say Superman can navigate by using the stars as reference points, after all he can’t just see where he’s headed, the curvature of the Earth would get in the way. Even then he would be pretty useless without one of these:

On first glance a sextant looks like the bastard child of a vernier caliper and a telescope, and to be fair, it kind of is. The only thing a sextant does is measure the angle something in the sky makes with the horizon. It can also be used to measure the angle between two objects in the sky.

This measurement is pretty useless on it’s own but with a star chart and time of day, you can do some pretty neat things. If you sight the sun at noon, or the North Star at night, you can estimate your latitude. If you know the height of a landmark, (for instance a lighthouse), the angle and some quick trigonometry could tell you how far away from it you were.

You can also figure out your longitude by measuring the angle between the moon and other celestial objects. If you’re interested the history of the longitude on Wikipedia is a great read.

So if Superman was really using the stars to navigate, he would need to fly around with a sextant, a g-shock, and a shelf full of maps and charts. Clearly, we can do better.

On Rocks and Nukes⌗

A “ballistic” body is something that is guided purely during a brief initial phase of flight, with the subsequent trajectory subject to the whims of air resistance and gravity. Making things go ballistic has always been a staple of our species. We’re unnaturally efficient at turning the act of hurling objects into forms of entertainment, sustenance and warfare. It’s really no wonder that the computer itself was a byproduct of us trying to figure out where the things we’re flinging inevitably succumbs to the omnipresent shackle of the Earth’s gravity. The kind of computation the Hulk would have to do before he just jumps really hard and lands exactly where he intends to.

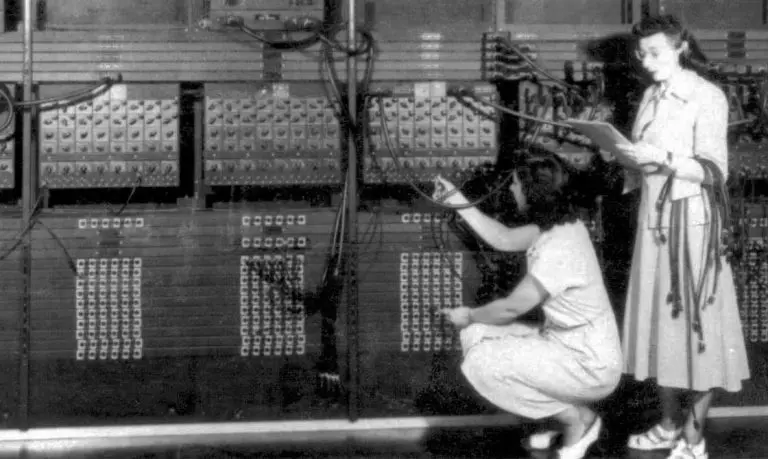

23 years after the development of the first aeronautical sextant, the ENIAC was built. It was the world’s first programmable computer and was originally designed to calculate artillery firing tables. Pretty soon the ENIAC shifted it’s focus to simulating the randomness of nuclear decay, something that makes a lot of sense when you realise that the ENIAC was built in 1945, a rather explosive time to be alive. The Monte Carlo simulation run on the ENIAC was written by Klara Dan von Neumann. She also developed the world’s first weather forecast on the ENIAC.

The ENIAC was the beginning of the rapidly shrinking size of computing machines, and was retired after 70000 hours of use. Later iterations like the EDVAC and ORDVAC worked in binary unlike the ENIAC which was still built around the biological and cultural simplicity of base 10. Development on both of them continued in the Ballistic Research Laboratory. Computers would go on to become a indispensable tool that they are now, and if Superman wants to go anywhere, he’ll need one.

Apart from ENIAC’s six primary programmers, Kay McNulty, Betty Jennings, Betty Snyder, Marlyn Wescoff, Fran Bilas and Ruth Lichterman, one of the people who oversaw the development of the ENIAC was John von Neumann. A name that pops up in so many different seemingly unrelated places, that one could be forgiven for assuming that they were different people. Merely listing out his contributions would make anyone feel like their life is going nowhere.

The ridiculous thing about Jon von Neumann was that he wasn’t alone. You see John was a part of a very exclusive club of prominent scientists that had all emigrated from Budapest, fearing the rapidly growing threat of Nazism. Many of them, including John von Neumann, Eugene Wigner, Leo Szilard, Edward Teller, and Theodore von Kármán, were friends since high school, studied similar subjects, and even attended some of the same universities in Germany. Each one of them was so extraordinarily brilliant that their peers hypothesised they must have come from another planet, and were known as “The Martians”. Edward Teller in particular was rather fond of his monogram (E.T). I can’t help but mention that Jon von Neumann was also Klara Dan von Neumann’s husband. If you’ve forgotten already, she wrote the first Monte Carlo simulation on the ENIAC. They would both go on to work on the MANIAC 1 computer together. They met at a casino in Monte Carlo where Jon explained that he had perfected a way to ensure that you could win roulette every time, and promptly lost all his money trying to prove his point. Afterwards, he asked Klara to buy him a drink.

Speaking of Mars, how do we get there?

Falling in style⌗

It was Newton’s prediction of the motion of the moon (not an apple) that proved his equation of gravity. An entire army of astronomers including Newton himself continued working on orbital mechanics. All of this was partly in an effort to predict the Moon’s position to two arc-minutes which would result in a 1° error in measuring the longitude on Earth.

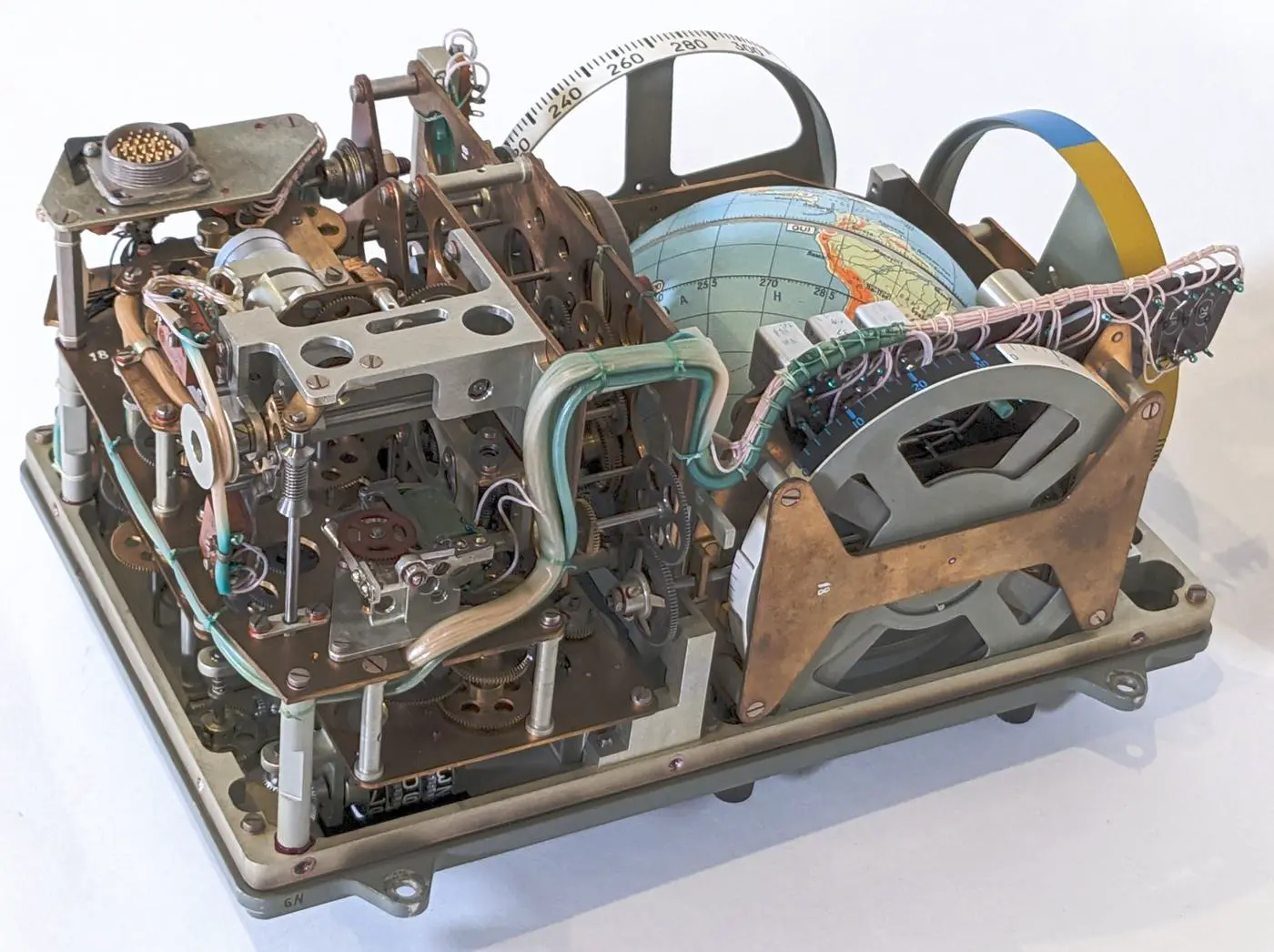

If Superman’s flight is like climbing an invisible ladder, then he doesn’t have to bother with the complexity of orbits. But that would also mean that early navigation systems built for space travel would be useless for Superman. Like the Soviet “Globus” INK which was an almost entirely mechanical contraption with minimal electronics. It could pinpoint the location of a spacecraft above the Earth, and with the flip of a switch show the landing site if the spacecraft continued along its trajectory. But at the end of the day, its cogs and gears were designed to obey the rules of orbital motion, it didn’t actually know where it was (whatever that means). Of course, everything else is obeying these rules, Superman has to fly to where something is going to be, and not where it is.

In 1964, Gary Flandro noticed that a particularly unique alignment of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune would occur in the late 70s. Something that happens once every 175 years. You see, this alignment would allow a single spacecraft to visit all the outer planets using gravity assists. At the height of the space race (which America was losing rather spectacularly at the time), the goalpost needed to be shifted. JPL came up with something they called “The Grand Tour”, a squad of 4 probes that would visit all the outer planets. The project was later scaled down and on August 20th, 1977 Voyager 2 took off on a Titan IIIE rocket and Voyager 1 took off 16 days later.

Space is incredibly sparse. The total mass of the asteroid belt is merely 3% that of the moon, half of that mass is concentrated within the 4 dwarf planets within the asteroid belt. The real challenge of space travel, regardless of whether you follow an orbital trajectory, is less about dodging things that would get in the way, and more about finding something to crash into. Let’s say Superman can literally see where Neptune is, if Superman is on Earth, the information of Neptune’s position is 242 minutes old, because that’s how far away it is. The angular size of Neptune seen from Earth would be about 2 arc seconds in size. That’s the equivalent of aiming for a coin held 4 kilometres away. If Superman flew at the speed of light in a straight line towards Neptune, it would already moved by around 79,000 kilometres. Of course, Superman isn’t flying blind, he could constantly adjust where he’s headed, ending up with a rather inefficient pursuit trajectory (I’m not going to bother exploring what Superman would even see at light speed).

Voyager 2, took 12 years to reach Neptune. Both probes were designed to preserve the possibility of the Grand Tour, in case the other failed. Voyager 2 was specifically tasked to fly by Saturn’s moon Titan if Voyager 1 couldn’t. But when Voyager 1 successfully completed that objective, Voyager 2 was free to continue its journey, becoming the first (and only) spacecraft to visit both Uranus and Neptune. Voyager 2 fulfilled the vision of the Grand Tour, 25 years after it was first predicted.

After completing their primary missions, both Voyagers continued outward, eventually overtaking the older Pioneer probes to become the fastest objects ever made by humans. They are two of just five spacecraft on trajectories that will take them beyond the solar system. They will likely remain the fastest human-made objects for the next 175 years.

In 296,000 years Voyager 2 will be 4.3 light years away from Sirius, but it is headed nowhere in particular. All 5 interstellar probes wander aimlessly. All of them are powered by plutonium reactors, an element first synthesised at scale during the Manhattan Project, of which many of our Martians were a part of. The Martians, (like the titular kryptonian), had to leave behind their homes, uncertain about what was to come, accepting whatever role they could. The Polynesian mythologies, that served to guide their people for millenia, were dreamt up by those who had no idea where they were headed. Sometimes you don’t have to know where you’re going, only what you’re leaving behind.